Is Africa Polio-Free?

Eradicating Polio

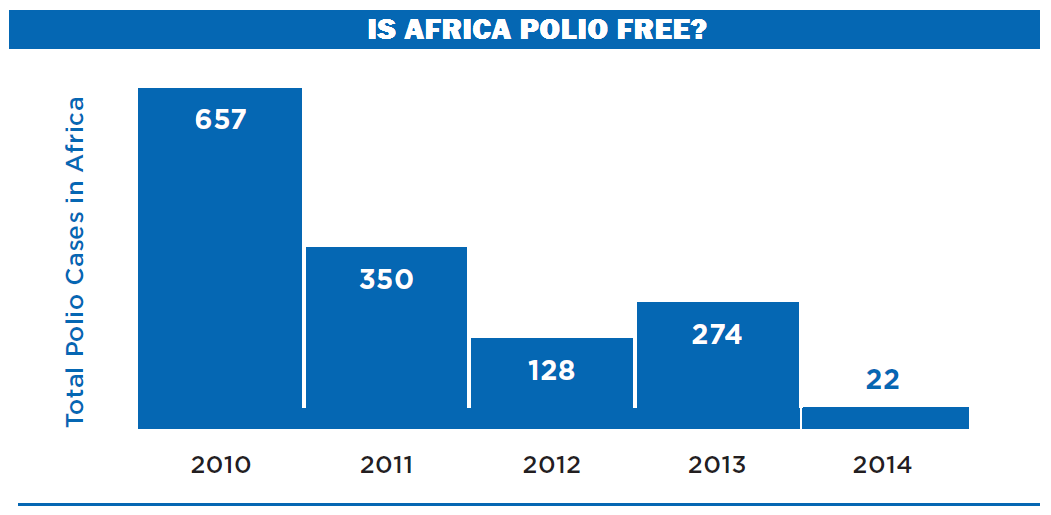

On 11 August 2015, for the first time in history, the entire African continent marked one year with no reported cases of wild poliovirus. This comes on the heels of the last reported case of wild polio virus in Africa’s last polio endemic country, Nigeria, in July 2014. But this progress is fragile. Samples remain in the laboratories from this one-year period which must be tested for the virus before we can be sure there has been no case, a process which takes around six weeks. Before the World Health Organization’s African Region can be certified polio-free, all countries must be free of the virus with reliable surveillance in place for at least the next two years. It is more important than ever that global, national and local leaders stay committed, that efforts remain focused on ensuring high-quality surveillance systems, and on reaching every last un- and under-immunized child.

Matshidiso Moeti, the regional director of WHO in Africa, said she was “deeply saddened” by the news. “The [Nigerian] government has made significant strides to stop this paralyzing disease in recent years. The overriding priority now is to rapidly immunize all children around the affected area and ensure that no other children succumb to this terrible disease.”